Sleep

Sorry, but Science Says You Should Not Sleep In on Weekends

Social jet lag from changing wakeup times can have the same effect as travel.

Posted May 3, 2024 Reviewed by Tyler Woods

Key points

- Changing wake up time affects circadian rhythms.

- This "social jet lag" alters physiology in a way similar to travel jet lag.

- Physical activity can help offset some, but not all, negative effects of changes in sleep timing.

Ever since I was writing Becoming Batman back in the mid-2000s and I was exploring the idea of what a nocturnal lifestyle would actually do to a human body, I got interested in what we now call “sleep hygiene," which is why a recent paper on sleep timing and the effects of “social jet lag” caught my eye.

I Wasn't Worried About Batman’s Bedtime

What fascinated me was what changing sleep patterns actually did to your body and brain, so much so that I wound up shifting my own personal practices to get away from something I'd done for a long time. And that something was a very common thing a lot of us do—try to catch up on the weekends by sleeping in.

I always felt kind of off when I did that. Later, I realized I felt kind of like I did when traveling and having jet lag. Regardless, I did it anyway but eventually I changed my wake up time to be the same every day of the week. This was mostly to align with my morning martial arts training regimen, but I began to notice I felt a lot better.

The reason I felt a lot better turns out to be due to something called “social jet lag.” It has been known for some time that changing your sleep patterns on the weekend does have an impact on the rest of your weekend. But it's only recently that the mechanisms underlying this have been discovered. This is why I found a recent paper published to be very interesting. It's in mice, and the extension to humans needs to be established, but the basic principles are likely very similar because mechanisms of something critical like sleep regulation are typically evolutionarily conserved across species.

Wake up and get out of bed, but do more than drag a comb across your head

Ambient light levels and physical exercise are both powerful factors for resetting and entraining our circadian rhythms. Both of these can be disrupted by changes in wake-up times that might occur in real “jet lag” from travel to a different part of the world or as induced by altering sleep hygiene deliberately. Michael Dial and colleagues at the University of Nevada were interested in the role that physical activity could have in altering such health problems as blood glucose regulation, body weight control, and diabetes. To truly control all the factors as much as possible, they used a mouse model.

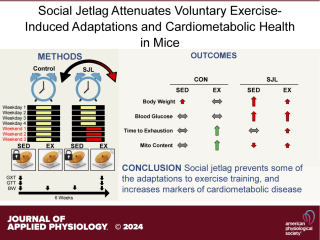

Dial and colleagues assigned mice to four groups of exercise or sedentary and with social jet lag or consistent wake times. As a bit of a bonus for the mice in the social jet lag group, they were given a simulated three-day weekend and allowed a four-hour wake-up delay before reverting back on "Monday."

They tested fitness on a graded wheel running protocol, assessed blood glucose tolerance, and measured muscle genetic clock mitochondrial functioning before and after a six-week intervention. The mice in the sleep-in group had impaired physical fitness, glucose handling, and body weight regulation.

Physical activity helped offset some of the negative effects of sleeping in, but not completely. The overall conclusion from this work is that regular alteration of wake-up timing "blunted cardiometabolic adaptations to exercise and that proper circadian hygiene is necessary for maintaining health and performance." Just like physically-induced jet lag, "social jet lag seems to be a potent circadian rhythm disruptor that impacts exercise-induced training adaptations."

Your brain cares most about when you wake up

All of this aligns with my own experiences since deciding to maintain my wake-up time no matter where I go or what time zone I'm in. The light cues and levels of physical activity, evolutionary signals telling your brain and body that you're alive and moving around, are the main drivers of anchoring our circadian rhythms and our daily functioning levels. So I just try to get right back on the horse and do my normal thing the very next day I arrive somewhere as I do wherever and whenever I am. It's a bit tiring on the first day, but it seems to help when traveling and for daily functioning while staying in place.

Of course, no matter what you do, events can conspire against you. Social jet lag is actually forced upon citizens of every country that participates in the ridiculous "changing of the clocks" between daylight and standard time twice per year. Regardless of what Taylor Swift, who proclaimed "jet lag is a choice," says, we can't just choose not to believe in social or travel jet lag.

References

Dial MB, Malek EM, Cooper AR, Neblina GA, Vasileva NI, Hines DJ, McGinnis GR. Social jet lag impairs exercise volume and attenuates physiological and metabolic adaptations to voluntary exercise training. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2024 Apr 1;136(4):996-1006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00632.2023. Epub 2024 Mar 7. PMID: 38450426